A Journey of Deconstruction: Losing My Religion at an Evangelical University

Guest post from author R. Scott Okamoto

I didn’t go into teaching at an evangelical university expecting to lose my faith. I just thought I’d teach English, help students engage with literature, and maybe, just maybe, convince a few of them that reading non-Christian books and articles wouldn’t invite Satan into their hearts.

What I didn’t expect was that my time at EVU (in my book I lovingly refer to it as “EVU”) would make me question everything I’d believed about God, faith, and the institution that claimed to represent both. It turns out that sometimes, the best way to lose your religion is to get a job inside it.

The Evangelical Bubble: An Alternate Reality Where Facts Go to Die

At first, EVU seemed like any other small Christian college—chapel three times a week, dorm curfews, and an unwavering belief that a well-timed prayer could help you pass a test you didn’t study for. The students, God bless their well-intentioned hearts, arrived fresh from evangelical high schools where their worldview had been carefully curated to exclude anything too… worldly. You know, like evolution, systemic racism, or the idea that gay people might be regular human beings and not just an elaborate trick of the devil.

My job was to teach writing and critical thinking—two things that, I quickly realized, evangelical culture found highly suspicious. Critical thinking, after all, is a gateway drug to asking dangerous questions. Like: Why does God seem to share all my parents’ political views? or Why is this school ranked #170 in the country but acts like it’s Harvard with a side of Jesus? The problem was, once I started encouraging students to think critically, some of them actually did. And, as it turns out, asking questions is the first step toward deconstruction.

And then there were the students who absolutely refused to engage in anything resembling independent thought. Some would submit essays that read more like sermons than arguments, peppered with Bible verses and long-winded justifications for why America was God’s chosen country. A particularly memorable student wrote an entire paper arguing that climate change was a hoax because “God controls the weather, not Al Gore.” When I gently pointed out that scientific consensus disagreed, he responded with, “That’s just Satan trying to trick us.”

I realized then that, in this world, logic was optional and faith trumped facts every time.

“A Republican Vote Is a Vote for God” and Other Theological Revelations

So many Christians today are deconstructing because they’ve learned how evangelicalism has been complicit with electing the most unChristian presidential candidate in US history, but for me, something similar had happened before. One of the defining moments of my disillusionment came during the 2004 election. If you’ve ever wanted to see a perfect marriage of politics and theology, just drop by an evangelical university during election season. EVU students weren’t just pro-Bush; they were convinced that Jesus himself would be registered Republican. To suggest otherwise was tantamount to heresy. When I tried to facilitate discussions about things like poverty, war, or racial justice—things Jesus seemed to care about—students responded with the same bewilderment as if I’d asked them to consider Leviticus as a metaphor.

Then came the emails from parents. Oh, the emails. According to them, I was corrupting their children by suggesting that The Great Gatsby had anything to say about the American Dream beyond “God’s plan.” One particularly irate father accused me of “forcing liberal indoctrination” on his daughter because I had dared to assign a chapter of Gloria Naylor’s, The Women of Brewster Place. (Apparently, talking about the existence of queer people in our neighborhoods was “too political.” The administration, while polite, made it clear that my brand of “education”—one that encouraged students to think beyond the party line—was unwelcome. I realized then that EVU didn’t actually want educated students. They wanted indoctrinated ones.

This was also the time I started noticing how deeply racism was embedded into evangelical spaces. As an Asian American professor, I wasn’t exactly embraced as a spiritual authority. Students often asked where I was “really” from, assuming that I must have immigrated to the U.S. at some point (spoiler: I didn’t).

But it wasn’t just microaggressions. It was the outright erasure of nonwhite perspectives from the curriculum, the way students dismissed discussions of racial injustice as “liberal propaganda,” and the fact that many of them believed America had solved racism because Martin Luther King Jr. “had a dream.” There was a perverse kind of irony in being an English professor tasked with teaching critical thinking while surrounded by students who had been trained to reject any narrative that challenged their worldview.

The Art of Letting Go (and Getting the Hell Out)

By the time I reached the end of my tenure at EVU, I had fully deconstructed the Christianity I was raised in. I’d seen it for what it is, and I knew there had to be something better. It wasn’t just the politics, the racism, or the fear of academic rigor—it was the realization that the entire system was built on a foundation that required people not to think too hard.

There was a moment, late in my time at EVU, when I sat in a faculty meeting where a professor proposed that we should count Christian books like megachurch pastor Rick Warren’s The Purpose Driven Life as an academic source on par with peer-reviewed journals.

Leaving faith behind wasn’t easy. But here’s the thing: letting go of evangelicalism didn’t make my world smaller—it made it bigger. I found community outside the church, in people who valued justice, art, and critical thought. I learned that morality isn’t exclusive to religion and that spirituality doesn’t have to be tied to an institution obsessed with policing behavior.

I also learned that there’s a massive community of exvangelicals who have walked the same path—people who have traded certainty for curiosity, dogma for discovery. And that, perhaps, is the most freeing part of all: realizing that I was never alone in this journey.

And so, dear reader, if you find yourself questioning, wondering, or feeling like your faith no longer fits—lean into it. Faith should evolve. If it can’t stand up to scrutiny, maybe it’s not worth holding onto. And if you ever find yourself at an evangelical university, remember: a critical mind is a terrible thing to waste—but a fantastic way to set yourself free.

Scott Okamoto

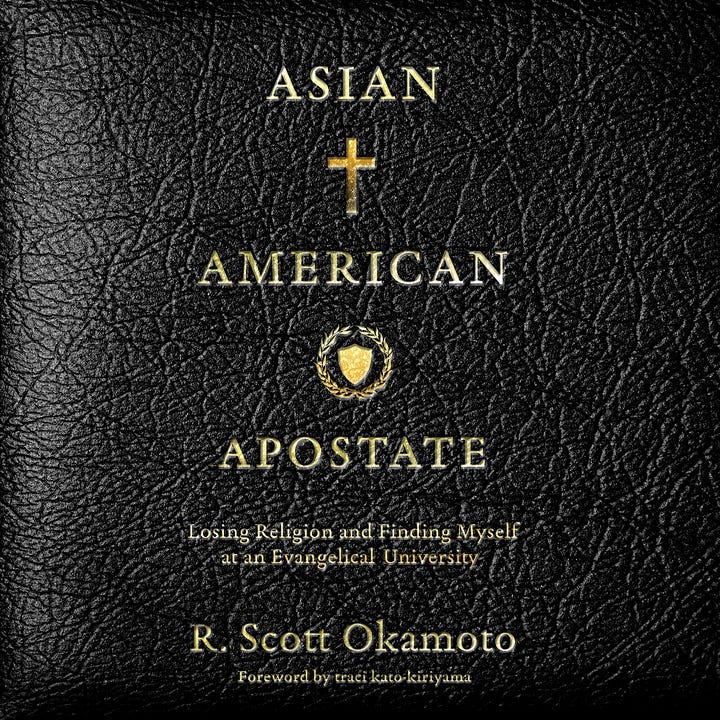

R. Scott Okamoto is a writer, musician, podcaster, and author of Asian American Apostate: Losing Religion and Finding Myself at an Evangelical University. A fourth-generation Japanese American (Yonsei), Okamoto holds an MA in writing, and much of his professional life involved teaching university-level English. He is the host of the series-based podcast Chapel Probation (Dauntless Media Collective). Okamoto is an avid fisher, GenX guitar player, poet, and participant in the Asian American artist community in Southern California, where he lives with his wife and three kids. Find out more at rscottokamoto.com.

Photo by Brett Jordan on Unsplash

Thanks for your support of Lake Drive Books. Would you consider sending this note to a friend? If you’re receiving this newsletter from a friend, be sure to sign up below and you’ll receive an opportunity to download one of our insightful audiobooks. Our newsletter is meant to inspire and inform, and along the way, we’ll make exclusive offers on our books to our newsletter subscribers.